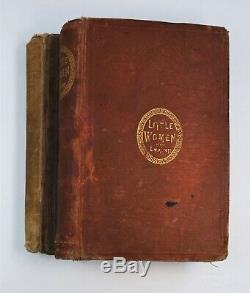

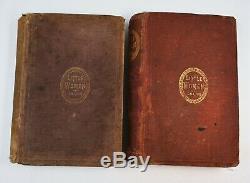

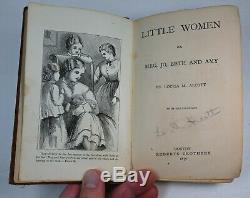

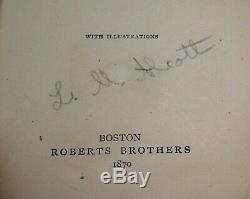

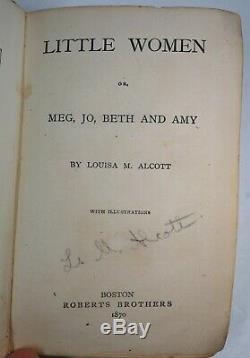

RARE 1870-71 Little Women First Edition Set 2 Parts SIGNED Louisa May Alcott

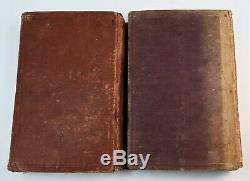

1870 (Part First) - 1st Edition of Set. 1871 (Part Second) - 2nd Edition of Set. For offer, a rare old book set. Fresh from an old prominent estate in Upstate, Western N. Never offered on the market until now.

These were found in a very old collector's library. I have my doubts, as she rarely signed books. Boston: Roberts Brothers, 1870, 1871. + publisher's advertising catalog at end of each volume. The set offered here is a matched set, with volume one a first edition of the set published in 1870 (as a set), and the second volume a second edition of the published set.

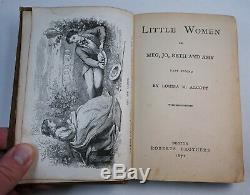

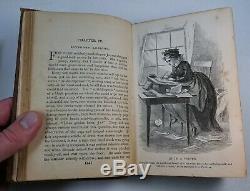

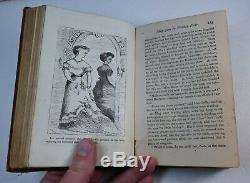

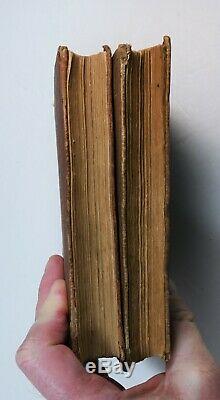

The true first edition of the first part was issued in 1868, and the second part in 1869. The 2 volume set was first offered in 1870. Wear to both volumes, wrinkle to spine of first volume; light age toning to some pages, with some minor foxing or small stains in some areas. Th volumes are in complete original condition.

Ee photos for details and feel free to ask any questions. F you collect 19th century Americana fiction, literature, autograph, American history, civil war era, classics, etc. This is a treasure you will not see again! Add this to your paper or ephemera collection. Little Women is a novel by American author Louisa May Alcott (18321888) which was originally published in two volumes in 1868 and 1869. Alcott wrote the book over several months at the request of her publisher. [1][2] Following the lives of the four March sistersMeg, Jo, Beth and Amythe novel details their passage from childhood to womanhood and is loosely based on the author and her three sisters. [3][4]:202 Scholars classify Little Women as an autobiographical or semi-autobiographical novel.Little Women was an immediate commercial and critical success, with readers demanding to know more about the characters. Alcott quickly completed a second volume (titled Good Wives in the United Kingdom, although this name originated from the publisher and not from Alcott). The two volumes were issued in 1880 as a single novel titled Little Women. Alcott wrote two sequels to her popular work, both of which also featured the March sisters: Little Men (1871) and Jo's Boys (1886). Little Women differed notably from contemporary writings for children, especially girls.

The novel addressed three major themes: domesticity, work, and true love, all of them interdependent and each necessary to the achievement of its heroine's individual identity. Little Women has been read as a romance or as a quest, or both. It has been read as a family drama that validates virtue over wealth, " but also "as a means of escaping that life by women who knew its gender constraints only too well. [8]:34 According to Sarah Elbert, Alcott created a new form of literature, one that took elements from Romantic children's fiction and combined it with others from sentimental novels, resulting in a totally new format.Elbert argued that within Little Women can be found the first vision of the "All-American girl" and that her various aspects are embodied in the differing March sisters. The book has frequently been adapted for stage and screen. In 1868, Thomas Niles, the publisher of Louisa May Alcott, recommended that she write a book about girls that would have widespread appeal. [4]:2 At first she resisted, preferring to publish a collection of her short stories. Niles pressed her to write the girls' book first, and he was aided by her father Amos Bronson Alcott, who also urged her to do so.

[4]:207 Louisa confided to a friend, I could not write a girls story knowing little about any but my own sisters and always preferring boys, as quoted in Anne Boyd Rioux's Meg Jo Beth Amy, a condensed biographical account of Alcott's life and writing. In May 1868, Alcott wrote in her journal: Niles, partner of Roberts, asked me to write a girl's book.

I said I'd try. [9]:36 Alcott set her novel in an imaginary Orchard House modeled on her own residence of the same name, where she wrote the novel.

[4]:xiii She later recalled that she did not think she could write a successful book for girls and did not enjoy writing it. [10]:335- "I plod away, " she wrote in her diary, although I don't enjoy this sort of things. By June, Alcott had sent the first dozen chapters to Niles, and both agreed these were dull.

But Niles' niece Lillie Almy read them and said she enjoyed them. [10]:335336 The completed manuscript was shown to several girls, who agreed it was splendid. Alcott wrote, they are the best critics, so I should definitely be satisfied. Explanation of the novel's title. According to literary critic Sarah Elbert, when using the term "little women", Alcott was drawing on its Dickensian meaning; it represented the period in a young woman's life where childhood and elder childhood were "overlapping" with young womanhood.

Each of the March sister heroines had a harrowing experience that alerted her and the reader that "childhood innocence" was of the past, and that "the inescapable woman problem" was all that remained. Other views suggest that the title was meant to highlight the unfair social inferiority, especially at that time, of women as compared to men, or, alternatively, describe the lives of simple people, "unimportant" in the social sense.

To comply with the Wikipedia quality standards, this book-related article may require cleanup. This article contains very little context, or is unclear to readers who know little about the book.

See this article's talk page before making any large and/or controversial edits. Four teenaged sisters and their mother, whom they call Marmee, live in a new neighborhood (loosely based on Concord) in Massachusetts in genteel poverty. The women face their first Christmas without him.Meg and Jo March, the elder two, have to work in order to support the family: Meg teaches a nearby family of four children; Jo assists her aged great-aunt March, a wealthy widow living in a mansion, Plumfield. Beth, too timid for school, is content to stay at home and help with housework; Amy is still at school. Meg is beautiful and traditional, Jo is a tomboy who writes; Beth is a peacemaker and a pianist; Amy is an artist who longs for elegance and fine society.

Jo is impulsive and quick to anger. One of her challenges is trying to control her anger, a challenge that her mother experiences. She advises Jo to speak with forethought before leaving to travel to Washington, where her husband has pneumonia.

Laurence, who is charmed by Beth, gives her a piano. Beth contracts scarlet fever after spending time with a poor family where three children die. Jo tends Beth in her illness. Beth recovers, but never fully.As a precaution, Amy is sent to live with Aunt March, replacing Jo, while Beth is ill and still infectious. Meg spends two weeks with friends, where there are parties for the girls to dance with boys and improve social skills. Laurence's grandson, is invited to one of the dances, as Meg's friends incorrectly think she is in love with him. Meg is more interested in John Brooke, Laurie's young tutor.

Brooke goes to Washington to help Mr. While with the March parents, Brooke confesses his love for Meg. They are pleased but consider Meg too young to be married.Brooke agrees to wait but enlists and serves a year or so in the war. Laurie goes off to college. (Published separately in the United Kingdom as Good Wives).

Three years later, Meg and John marry and learn how to live together. When they have twins, Meg is a devoted mother but John begins to feel left out. Laurie graduates from college, having put in effort to do well in his last year with Jo's prompting. Amy goes on a European tour with her aunt and Beth's health is weak and her spirits are down.When trying to uncover the reason for Beth's sadness, Jo realizes that Laurie has fallen in love. At first she believes it's with Beth but soon senses it's with herself. Jo confides in Marmee, telling her that she loves Laurie but she loves him like a brother and that she could not love him the romantic way. Jo decides she wants a bit of adventure and wants to put distance between herself and Laurie, hoping he forgets his feelings.

She spends six months with a friend of her mother in New York City, serving as governess for her two children. The family runs a boarding house. She takes German lessons with Professor Bhaer, who lives in the house. He has come to America from Berlin to care for the orphaned sons of his sister. He persuades her to give up poorly written sensational stories as her time in New York comes to an end.

Laurie travels to Europe with his grandfather to escape his heartbreak. At home, Beth's health has seriously deteriorated. Jo devotes her time to the care of her dying sister. Laurie encounters Amy in Europe, and he slowly falls in love with her as Laurie begins to see Amy in a new light. However, she is unimpressed by the aimless, idle and forlorn attitude he had adopted after being rejected by Jo, and inspires him to find his purpose and do something worthwhile with his life.

With the news of Beth's death, they meet for consolation and their romance grows. Amy's aunt will not allow Amy to return with just Laurie and his grandfather, so they marry before returning home from Europe. Professor Bhaer goes to the Marches' and stays for two weeks. On his last day, he proposes to Jo. When Aunt March dies, she leaves Plumfield to Jo.

She and Bhaer turn the house into a school for boys. They have two sons of their own, and Amy and Laurie have a daughter. At the apple-picking time, Marmee celebrates her 60th birthday at Plumfield, with her husband, her three surviving daughters, their husbands, and her five grandchildren. Meg, the eldest sister, is 16 when the story starts. She is referred to as a beauty and manages the household when her mother is absent.

According to Alcott's description of the character, she is brown-haired and blue-eyed and has particularly beautiful hands. Meg fulfills expectations for women of the time; from the start, she is already a nearly perfect "little woman" in the eyes of the world.Meg is based in the domestic household; she does not have significant employment or activities outside it. [13] Before her marriage to John Brooke, while still living at home, she often lectures her younger sisters to ensure they grow to embody the title of "little women".

Meg is employed as a governess for the Kings, a wealthy local family. Because of their father's family's social standing, Meg makes her debut into high society, but is lectured by her friend and neighbor, Theodore "Laurie" Laurence, for behaving like a snob. Meg marries John Brooke, the tutor of Laurie.They have twins, Margaret "Daisy" Brooke and John "Demi" Brooke. The sequel, Little Men, mentions a baby daughter, Josephine "Josy" Brooke, [15] who is 14 at the beginning of the final book. Critics have portrayed Meg as lacking in independence, reliant entirely on her husband, and "isolated in her little cottage with two small children".

[7]:204 From this perspective, Meg is seen as the compliant daughter who does not "attain Alcott's ideal womanhood" of equality. According to Sarah Elbert, "democratic domesticity requires maturity, strength, and above all a secure identity that Meg lacks".

[7]:204 Others believe that Alcott does not intend to belittle Meg for her ordinary life, and portrays her in loving details, suffused in a sentimental light. The principal character, Jo, 15 years old at the beginning of the book, is a strong and willful young woman, struggling to subdue her fiery temper and stubborn personality. The second oldest of four sisters, Josephine March is the boyish one; her father has referred to her as his "son Jo, " and her best friend and neighbor, Theodore "Laurie" Laurence, sometimes calls her "my dear fellow, " while she alone calls him Teddy.

Jo has a "hot" temper that often leads her into trouble. With the help of her own misguided sense of humor, her sister Beth, and her mother, she works on controlling it. It has been said that much of Louisa May Alcott shows through in these characteristics of Jo. Jo loves literature, both reading and writing. She composes plays for her sisters to perform and writes short stories.She initially rejects the idea of marriage and romance, feeling that it would break up her family and separate her from the sisters whom she adores. While pursuing a literary career in New York City, she meets Friedrich Bhaer, a German professor.

On her return home, Jo rejects Laurie's marriage proposal, confirming her independence. After Beth dies, Professor Bhaer woos Jo at her home, when They decide to share life's burdens just as they shared the load of bundles on their shopping expedition. [7]:210 She is 25 years old when she accepts his proposal.

The marriage is deferred until her unexpected inheritance of her Aunt March's home a year later. According to critic Barbara Sicherman, The crucial first point is that the choice is hers, its quirkiness another sign of her much-prized individuality. "[8]:21 They have two sons, Robin "Rob" Bhaer and Theodore "Teddy Bhaer. Jo also writes the first part of Little Women during the second portion of the novel.

According to Elbert, "her narration signals a successfully completed adolescence". Beth, 13 when the story starts, is described as kind, gentle, sweet, shy, quiet and musical. She is the shyest March sister. [21]:53 Infused with quiet wisdom, she is the peacemaker of the family and gently scolds her sisters when they argue. [22] As her sisters grow up, they begin to leave home, but Beth has no desire to leave her house or family. She is especially close to Jo: when Beth develops scarlet fever after visiting the Hummels, Jo does most of the nursing and rarely leaves her side. Beth recovers from the acute disease but her health is permanently weakened.As she grows, Beth begins to realize that her time with her loved ones is coming to an end. Finally, the family accepts that Beth will not live much longer. They make a special room for her, filled with all the things she loves best: her kittens, piano, Father's books, Amy's sketches, and her beloved dolls. She is never idle; she knits and sews things for the children who pass by on their way to and from school. But eventually she puts down her sewing needle, saying it grew heavy.

Beth's final sickness has a strong effect on her sisters, especially Jo, who resolves to live her life with more consideration and care for everyone. The main loss during Little Women is the death of beloved Beth. Her "self-sacrifice" is ultimately the greatest in the novel. She gives up her life knowing that it has had only private, domestic meaning.Amy is the youngest sister and baby of the family, aged 12 when the story begins. Interested in art, she is described as a "regular snow-maiden" with curly golden hair and blue eyes, "pale and slender" and "always carrying herself" like a proper young lady. She is the artist of the family.

[23] Often coddled because she is the youngest, Amy can behave in a vain and self-centered way. [24]:5 She has the middle name Curtis, and is the only March sister to use her full name rather than a diminutive. She is chosen by her aunt to travel in Europe with her, where she grows and makes a decision about the level of her artistic talent and how to direct her adult life. She encounters "Laurie" Laurence and his grandfather during the extended visit. Amy is the least inclined of the sisters to sacrifice and self-denial.

She behaves well in good society, at ease with herself. Critic Martha Saxton observes the author was never fully at ease with Amy's moral development and her success in life seemed relatively accidental. [24] However, Amy's morality does appear to develop throughout her adolescence and early adulthood, and she is able to confidently and justly put Laurie in his place when she believes he is wasting his life on the pleasurable activity. Ultimately, Amy is shown to work very hard to gain what she wants in life, and to make the most of her success while she has it. Due to her early selfishness (when her friends knew she would not share any pickled lime) and attachment to material things, Amy has been described as the least likable of the four sisters, but she is also the only one who strives to excel at art purely for self-expression, in contrast to Jo, who sometimes writes for financial gain.The March Sisters by Pablo Marcos. Margaret "Marmee" March The girls' mother and head of household while her husband is away. She engages in charitable works and lovingly guides her girls' morals and their characters. She once confesses to Jo that her temper is as volatile as Jo's, but that she has learned to control it. [27]:130 Somewhat modeled after the author's own mother, she is the focus around which the girls' lives unfold as they grow.

Robert March Formerly wealthy, the father is portrayed as having helped friends who could not repay a debt, resulting in his family's genteel poverty. A scholar and a minister, he serves as a chaplain in the Union Army during the Civil War and is wounded in December 1862.

After the war he becomes minister to a small congregation. Professor Friedrich Bhaer A middle-aged, "philosophically inclined", and penniless German immigrant in New York City who was a noted professor in Berlin, also known as Fritz.

He initially lives in Mrs. Kirke's boarding house and works as a language master. [21]:61 He and Jo become friends, and he critiques her writing.

He encourages her to become a serious writer instead of writing sensational stories for weekly tabloids. Bhaer has all the qualities Bronson Alcott lacked: warmth, intimacy, and a tender capacity for expressing his affectionthe feminine attributes Alcott admired and hoped men could acquire in a rational, feminist world. [7]:210 They eventually marry and raise his two orphaned nephews, Franz and Emil, and their own sons, Rob and Teddy. Robin and Theodore Bhaer ("Rob" and "Teddy") Jo's and Fritz's sons, introduced in the final pages of the novel, named after the March girls' father and Laurie.John Brooke During his employment as a tutor to Laurie, he falls in love with Meg. When her husband is ill with pneumonia. When Laurie leaves for college, Brooke continues his employment with Mr. When Aunt March overhears Meg rejecting John's declaration of love, she threatens Meg with disinheritance because she suspects that Brooke is only interested in Meg's future prospects. Eventually, Meg admits her feelings to Brooke, they defy Aunt March (who ends up accepting the marriage), and they are engaged.

Brooke serves in the Union Army for a year and is sent home as an invalid when he is wounded. Brooke marries Meg a few years later when the war has ended and she has turned twenty.Brooke was modeled after John Bridge Pratt, her sister Anna's husband. Margaret and John Laurence Brooke ("Daisy" and "Demijohn/Demi") Meg's twin son and daughter. Daisy is named after both Meg and Marmee, while Demi is named for John and the Laurence family. Josephine Brooke ("Josy" or "Josie") Meg's youngest child, named after Jo. She develops a passion for acting as she grows up.

Uncle and Aunt Carrol Sister and brother-in-law of Mr. They take Amy to Europe with them, where Uncle Carrol frequently tries to be like an English gentleman.Florence "Flo" Carrol Amy's cousin, daughter of Aunt and Uncle Carrol, and companion in Europe. Chester A well-to-do family with whom the Marches are acquainted. May Chester is a girl about Amy's age, who is rich and jealous of Amy's popularity and talent. Miss Crocker An old and poor spinster who likes to gossip and who has few friends.

Dashwood Publisher and editor of the Weekly Volcano. Davis The schoolteacher at Amy's school. He punishes Amy for bringing pickled limes to school by striking her palm and making her stand on a platform in front of the class.

She is withdrawn from the school by her mother. Estelle "Esther" Valnor A French woman employed as a servant for Aunt March who befriends Amy.

The Gardiners Wealthy friends of Meg's. Sallie Gardiner is a well-to-do friend of Meg's who later marries Ned Moffat. The Hummels A poor German family consisting of a widowed mother and six children. Marmee and the girls help them by bringing food, firewood, blankets, and other comforts.They help with minor repairs to their small dwelling. Three of the children die of scarlet fever and Beth contracts the disease while caring for them. The eldest daughter, Lottchen "Lotty" Hummel, later works as a matron at Jo's school at Plumfield. The Kings A wealthy family with four children for whom Meg works as a governess.

Kirke is a friend of Mrs. March's who runs a boarding house in New York. She employs Jo as governess to her two daughters, Kitty and Minnie.

The Lambs A well-off family with whom the Marches are acquainted. James Laurence Laurie's grandfather and a wealthy neighbor of the Marches.

Lonely in his mansion, and often at odds with his high-spirited grandson, he finds comfort in becoming a benefactor to the Marches. He protects the March sisters while their parents are away. He was a friend to Mrs. March's father, and admires their charitable works.He develops a special, tender friendship with Beth, who reminds him of his late granddaughter. He gives Beth the girl's piano. Theodore "Laurie" Laurence A rich young man who lives opposite the Marches, older than Jo but younger than Meg. Laurie is the "boy next door" to the March family and has an overprotective paternal grandfather, Mr. After eloping with an Italian pianist, Laurie's father was disowned by his parents.

Both Laurie's mother and father died young, so as a boy Laurie was taken in by his grandfather. Preparing to enter Harvard, Laurie is being tutored by John Brooke. He is described as attractive and charming, with black eyes, brown skin, and curly black hair. He later falls in love with Amy and they marry; they have one child, a little girl named after Beth: Elizabeth "Bess" Laurence.

Sometimes Jo calls Laurie "Teddy". Though Alcott did not make Laurie as multidimensional as the female characters, she partly based him on Ladislas Wisniewski, a young Polish émigré she had befriended, and Alf Whitman, a friend from Lawrence, Kansas. [4]:202[6]:241[24]:287 According to author and professor Jan Susina, the portrayal of Laurie is as "the fortunate outsider", observing Mrs. March and the March sisters. He agrees with Alcott that Laurie is not strongly developed as a character.

Elizabeth Laurence ("Bess") The only daughter of Laurie and Amy, named for Beth. Like her mother, she develops a love for art as she grows up. March's aunt, a rich widow.Somewhat temperamental and prone to being judgmental, she disapproves of the family's poverty, their charitable work, and their general disregard for the more superficial aspects of society's ways. Her vociferous disapproval of Meg's impending engagement to the impoverished Mr. Brooke becomes the proverbial "last straw" that actually causes Meg to accept his proposal. She appears to be strict and cold, but deep down, she's really quite soft-hearted.

She dies near the end of the first book, and Jo and Friedrich turn her estate into a school for boys. Annie Moffat A fashionable and wealthy friend of Meg and Sallie Gardiner. Ned Moffat Annie Moffat's brother, who marries Sallie Gardiner.

Hannah Mullet The March family maid and cook, their only servant. She is of Irish descent and very dear to the family. She is treated more like a member of the family than a servant. Miss Norton A friendly, well-to-do tenant living in Mrs.She occasionally invites Jo to accompany her to lectures and concerts. Susie Perkins A girl at Amy's school. The Scotts Friends of Meg and John Brooke. Tina The young daughter of an employee of Mrs. Bhaer and treats him like a father.

The Vaughans English friends of Laurie's who come to visit him. Kate is the oldest of the Vaughn siblings, and prim and proper Grace is the youngest. The middle siblings, Fred and Frank, are twins; Frank is the younger twin. Fred Vaughan A Harvard friend of Laurie's who, in Europe, courts Amy. Rivalry with the much richer Fred for Amy's love inspires the dissipated Laurie to pull himself together and become more worthy of her.Amy will eventually reject Fred, knowing she does not love him and deciding not to marry out of ambition. Frank Vaughan Fred's twin brother, mentioned a few times in the novel.

When Fred and Amy are both travelling in Europe, Fred leaves because he heard his twin is ill. The attic at Fruitlands where Alcott lived and acted out plays at 11 years old. Note that the ceiling area is around 4 feet high. For her books, Alcott was often inspired by familiar elements. The characters in Little Women are recognizably drawn from family members and friends.[3][4]:202 Her married sister Anna was Meg, the family beauty. Lizzie, Alcott's beloved sister who died at the age of twenty-three, was the model for Beth, and May, Alcott's strong-willed sister, was portrayed as Amy, whose pretentious affectations cause her occasional downfalls. [4]:202 Alcott portrayed herself as Jo.

Alcott readily corresponded with readers who addressed her as "Miss March" or "Jo", and she did not correct them. However, Alcott's portrayal, even if inspired by her family, is an idealized one. March is portrayed as a hero of the American Civil War, a gainfully employed chaplain, and, presumably, a source of inspiration to the women of the family. He is absent for most of the novel. [33]:51 In contrast, Bronson Alcott was very present in his family's household, due in part to his inability to find steady work.While he espoused many of the educational principles touted by the March family, he was loud and dictatorial. His lack of financial independence was a source of humiliation to his wife and daughters. [33]:51 The March family is portrayed living in genteel penury, but the Alcott family, dependent on an improvident, impractical father, suffered real poverty and occasional hunger. [34] In addition to her own childhood and that of her sisters, scholars who have examined the diaries of Louisa Alcott's mother, Abigail Alcott, have surmised that Little Women was also heavily inspired by Abigail Alcott's own early life. The first volume of Little Women was published in 1868 by Roberts Brothers.

They announced: The great literary hit of the season is undoubtedly Miss Alcott's Little Women, the orders for which continue to flow in upon us to such an extent as to make it impossible to answer them with promptness. "[9]:37 The last line of Chapter 23 in the first volume is "So the curtain falls upon Meg, Jo, Beth, and Amy. Whether it ever rises again, depends upon the reception given the first act of the domestic drama called Little Women. [36] Alcott delivered the manuscript for the second volume on New Year's Day 1869, just three months after publication of part one. Versions in the late 20th and 21st centuries combine both portions into one book, under the title Little Women, with the later-written portion marked as Part 2, as this Bantam Classic paperback edition, initially published in 1983 typifies.

[37] There are 23 chapters in Part 1 and 47 chapters in the complete book. Each chapter is numbered and has a title as well.

Part 2, Chapter 24 opens with In order that we may start afresh and go to Meg's wedding with free minds, it will be well to begin with a little gossip about the Marches. [36] Editions published in the 21st century may be the original text unaltered, the original text with illustrations, the original text annotated for the reader (explaining terms of 186869 that are less common now), the original text modernized and abridged, the original text abridged. The British influence, giving Part 2 its own title, Good Wives, has the book still published in two volumes, with Good Wives beginning three years after Little Women ends, especially in the UK and Canada, but also with some US editions. Some editions listed under Little Women appear to include both parts, especially in the audio book versions. [38] Editions are shown in continuous print from many publishers, as hardback, paperback, audio, and e-book versions, from the 1980s to 2015.

[38][39] This split of the two volumes also shows at Goodreads, which refers to the books as the Little Women series, including Little Women, Good Wives, Little Men and Jo's Boys. Chesterton notes that in Little Women, Alcott "anticipated realism by twenty or thirty years", and that Fritz's proposal to Jo, and her acceptance, is one of the really human things in human literature. Jackson said that Alcott's use of realism belongs to the American Protestant pedagogical tradition, which includes a range of religious literary traditions with which Alcott was familiar. He has copies in his book of nineteenth-century images of devotional children's guides which provide background for the game of "pilgrims progress" that Alcott uses in her plot of Book One. When Little Women was published, it was well received.

According to 21st-century critic Barbara Sicherman, during the 19th century, there was a "scarcity of models for nontraditional womanhood", which led more women to look toward literature for self-authorization. This is especially true during adolescence. "[8]:2 Little Women became "the paradigmatic text for young women of the era and one in which family literary culture is prominently featured. "[8]:3 Adult elements of women's fiction in Little Women included "a change of heart necessary for the female protagonist to evolve in the story. In late 20th century, some scholars have criticized the novel.

Sarah Elbert, for instance, wrote that Little Women was the beginning of "a decline in the radical power of women's fiction", partly because women's fiction was being idealized with a "hearth and home" children's story. [7]:197 Women's literature historians and juvenile fiction historians have agreed that Little Women was the beginning of this "downward spiral". But Elbert says that Little Women did not "belittle women's fiction" and that Alcott stayed true to her "Romantic birthright". Little Women's popular audience was responsive to ideas of social change as they were shown "within the familiar construct of domesticity".

[7]:220 While Alcott had been commissioned to "write a story for girls", her primary heroine, Jo March, became a favorite of many different women, including educated women writers through the 20th century. The girl story became a "new publishing category with a domestic focus that paralleled boys' adventure stories". One reason the novel was so popular was that it appealed to different classes of women along with those of different national backgrounds, at a time of high immigration to the United States.Through the March sisters, women could relate and dream where they may not have before. [8]:34 Both the passion Little Women has engendered in diverse readers and its ability to survive its era and transcend its genre point to a text of unusual permeability.

At the time, young girls perceived that marriage was their end goal. After the publication of the first volume, many girls wrote to Alcott asking her "who the little women marry". [8]:21 The unresolved ending added to the popularity of Little Women.

Sicherman said that the unsatisfying ending worked to "keep the story alive" as if the reader might find it ended differently upon different readings. [8]:21 Alcott particularly battled the conventional marriage plot in writing Little Women.

[43] Alcott did not have Jo accept Laurie's hand in marriage; rather, when she arranged for Jo to marry, she portrayed an unconventional man as her husband. Alcott used Friedrich to "subvert adolescent romantic ideals" because he was much older and seemingly unsuited for Jo.

In 2003 Little Women was ranked number 18 in The Big Read, a survey of the British public by the BBC to determine the "Nation's Best-loved Novel" (not children's novel); it is fourth-highest among novels published in the U. [44] Based on a 2007 online poll, the U. National Education Association named it one of "Teachers' Top 100 Books for Children". [45] In 2012 it was ranked number 48 among all-time children's novels in a survey published by School Library Journal, a monthly with primarily US audience.

Little Women has been one of the most widely read novels, noted by Stern from a 1927 report in the New York Times and cited in Little Women and the Feminist Imagination: Criticism, Controversy, Personal Essays. [47] Ruth MacDonald argued that Louisa May Alcott stands as one of the great American practitioners of the girls' novel and the family story. In the 1860s, gendered separation of children's fiction was a newer division in literature.

This division signaled a beginning of polarization of gender roles as social constructs "as class stratification increased". [8]:18 Joy Kasson wrote, Alcott chronicled the coming of age of young girls, their struggles with issues such as selfishness and generosity, the nature of individual integrity, and, above all, the question of their place in the world around them.

[49] Girls related to the March sisters in Little Women, along with following the lead of their heroines, by assimilating aspects of the story into their own lives. After reading Little Women, some women felt the need to "acquire new and more public identities", however dependent on other factors such as financial resources.

[8]:55 While Little Women showed regular lives of American middle-class girls, it also "legitimized" their dreams to do something different and allowed them to consider the possibilities. [8]:36 More young women started writing stories that had adventurous plots and stories of individual achievementtraditionally coded malechallenged women's socialization into domesticity.

[8]:55 Little Women also influenced contemporary European immigrants to the United States who wanted to assimilate into middle-class culture. In the pages of Little Women, young and adolescent girls read the normalization of ambitious women. This provided an alternative to the previously normalized gender roles. [8]:35 Little Women repeatedly reinforced the importance of "individuality" and "female vocation".

[8]:26 Little Women had "continued relevance of its subject" and its longevity points as well to surprising continuities in gender norms from the 1860s at least through the 1960s. "[8]:35 Those interested in domestic reform could look to the pages of Little Women to see how a "democratic household would operate. While "Alcott never questioned the value of domesticity", she challenged the social constructs that made spinsters obscure and fringe members of society solely because they were not married.[7]:193 Little Women indisputably enlarges the myth of American womanhood by insisting that the home and the women's sphere cherish individuality and thus produce young adults who can make their way in the world while preserving a critical distance from its social arrangements. As with all youth, the March girls had to grow up. These sisters, and in particular Jo, were apprehensive about adulthood because they were afraid that, by conforming to what society wanted, they would lose their special individuality.

Alcott's Jo also made professional writing imaginable for generations of women. Writers as diverse as Maxine Hong Kingston, Margaret Atwood, and J. Rowling have noted the influence of Jo March on their artistic development. Even other fictional portraits of young women aspiring to authorship often reference Jo March. Alcott made women's rights integral to her stories, and above all to Little Women. "[7]:193 Alcott's fiction became her "most important feminist contributioneven considering all the effort Alcott made to help facilitate women's rights. "[7]:193 She thought that "a democratic household could evolve into a feminist society. In Little Women, she imagined that just such an evolution might begin with Plumfield, a nineteenth century feminist utopia. Little Women has a timeless resonance which reflects Alcott's grasp of her historical framework in the 1860s. The novel's ideas do not intrude themselves upon the reader because the author is wholly in control of the implications of her imaginative structure. Sexual equality is the salvation of marriage and the family; democratic relationships make happy endings. This is the unifying imaginative frame of Little Women. Scene from the 1912 Broadway production of Little Women, adapted by Marian de Forest. Katharine Cornell became a star in the 1919 London production of de Forest's adaptation of Little Women. Marian de Forest adapted Little Women for the Broadway stage in 1912. [51] The 1919 London production made a star of Katharine Cornell, who played the role of Jo.A one-act stage version, written by Gerald P. Murphy in 2009, [53] has been produced in the US, UK, Italy, Australia, Ireland, and Singapore.

[citation needed] Myriad Theatre & Film adapted the novel as a full-length play which was staged in London and Essex in 2011. Marisha Chamberlain[55][56] and June Lowery[57] have both adapted the novel as a full-length play; the latter play was staged in Luxembourg in 2014. Isabella Russell-Ides created two stage adaptations.Her Little Women featured an appearance by author, Louisa May Alcott. Jo & Louisa features a rousing confrontation between the unhappy character, Jo March, who wants rewrites from her author. A new adaptation by award-winning playwright Kate Hamill had its world premiere in 2018 at the Jungle Theater in Minneapolis, followed by a New York premiere in 2019 at Primary Stages directed by Sarna Lapine. Little Women has been adapted to film seven times. The first adaptation was a silent film directed by Alexander Butler and released in 1917, which starred Daisy Burrell as Amy, Mary Lincoln as Meg, Ruby Miller as Jo, and Muriel Myers as Beth.

It is considered a lost film. Another silent film adaptation was released in 1918 and directed by Harley Knoles.

It starred Isabel Lamon as Meg, Dorothy Bernard as Jo, Lillian Hall as Beth, and Florence Flinn as Amy. George Cukor directed the first sound adaptation of Little Women, starring Katharine Hepburn as Jo, Joan Bennett as Amy, Frances Dee as Meg, and Jean Parker as Beth. The film was released in 1933 and followed by an adaptation of Little Men the year after. The first color adaptation starred June Allyson as Jo, Margaret O'Brien as Beth, Elizabeth Taylor as Amy, and Janet Leigh as Meg. Directed by Mervyn LeRoy, it was released in 1949. Gillian Armstrong directed a 1994 adaptation, which starred Winona Ryder as Jo, Trini Alvarado as Meg, Samantha Mathis and Kirsten Dunst as Amy, and Claire Danes as Beth. [61] The film received three Academy Award nominations, including Best Actress for Ryder. A contemporary film adaptation[62] was released in 2018 to mark the 150th anniversary of the novel. [63] It was directed by Clare Niederpruem in her directorial debut and starred Sarah Davenport as Jo, Allie Jennings as Beth, Melanie Stone as Meg, and Elise Jones and Taylor Murphy as Amy. A 2019 adaptation directed by Greta Gerwig starred Saoirse Ronan as Jo, Emma Watson as Meg, Florence Pugh as Amy, and Eliza Scanlen as Beth. Little Women was adapted into a television musical, in 1958, by composer Richard Adler for CBS. Little Women has been made into a serial four times by the BBC: in 1950 (when it was shown live), in 1958, in 1970, [66] and in 2017. [67] The 3-episode 2017 series development was supported by PBS, and was aired as part of the PBS Masterpiece anthology in 2018. Universal Television produced a two-part miniseries based on the novel, which aired on NBC in 1978. It was followed by a 1979 series. In the 1980s, two anime series were made in Japan, Little Women in 1981 and Tales of Little Women in 1987. Both anime series were dubbed in English and shown on American television.[68] It is usually rebroadcast on the channel each holiday season. A 2018 adaption is that of Balaji Telefilms in India.

The web series is called Haq Se. Set in Kashmir, the series is a modern-day Indian adaptation of the book.The novel was adapted to a musical of the same name and debuted on Broadway at the Virginia Theatre on January 23, 2005 and closed on May 22, 2005 after 137 performances. A production was also staged in Sydney, Australia in 2008. The Houston Grand Opera commissioned and performed Little Women in 1998. The opera was aired on television by PBS in 2001 and has been staged by other opera companies since the premiere.

There is a Canadian musical version, with book by Nancy Early and music and lyrics by Jim Betts, which has been produced at several regional theatres in Canada. There was another musical version, entitled "Jo", with music by William Dyer and book and lyrics by Don Parks & William Dyer, which was produced off-Broadway at the Orpheum Theatre. It ran for 63 performances from February 12, 1964, to April 5, 1964.It featured Karin Wolfe (Jo), Susan Browning (Meg), Judith McCauley (Beth), April Shawhan (Amy), Don Stewart (Laurie), Joy Hodges (Marmee), Lowell Harris (John Brooke) and Mimi Randolph (Aunt March). A radio play starring Katharine Hepburn as Jo was made to accompany the 1933 film. A dramatized version, produced by Focus on the Family Radio Theatre, [72] was released on September 4, 2012.

Hillside (later renamed The Wayside), the Alcott family home (18451848) and real-life setting for some of the book's scenes. Orchard House, the Alcott family home (18581877) and site where the book was written; adjacent to The Wayside.Louisa May Alcott (/lkt, -kt/; November 29, 1832 March 6, 1888) was an American novelist, short story writer and poet best known as the author of the novel Little Women (1868) and its sequels Little Men (1871) and Jo's Boys (1886). [1] Raised in New England by her transcendentalist parents, Abigail May and Amos Bronson Alcott, she grew up among many of the well-known intellectuals of the day, such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Henry David Thoreau, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow. Alcott's family suffered from financial difficulties, and while she worked to help support the family from an early age, she also sought an outlet in writing. She began to receive critical success for her writing in the 1860s. Early in her career, she sometimes used the pen name A.

Barnard, under which she wrote novels for young adults that focused on spies and revenge. Published in 1868, Little Women is set in the Alcott family home, Orchard House, in Concord, Massachusetts, and is loosely based on Alcott's childhood experiences with her three sisters, Abigail May Alcott Nieriker, Elizabeth Sewall Alcott, and Anna Alcott Pratt. The novel was well-received at the time and is still popular today among both children and adults.

It has been adapted many times to the stage, film, and television. Alcott was an abolitionist and a feminist and remained unmarried throughout her life. She died from a stroke, two days after her father died, in Boston on March 6, 1888.Louisa May Alcott was born on November 29, 1832, [1] in Germantown, [1] which is now part of Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, on her father's 33rd birthday. She was the daughter of transcendentalist and educator Amos Bronson Alcott and social worker Abby May and the second of four daughters: Anna Bronson Alcott was the eldest; Elizabeth Sewall Alcott and Abigail May Alcott were the two youngest. The family moved to Boston in 1834, [2] where Alcott's father established an experimental school and joined the Transcendental Club with Ralph Waldo Emerson and Henry David Thoreau. Bronson Alcott's opinions on education and tough views on child-rearing as well as his moments of mental instability shaped young Alcott's mind with a desire to achieve perfection, a goal of the transcendentalists.

[3] His attitudes towards Alcott's wild and independent behavior, and his inability to provide for his family, created conflict between Bronson Alcott and his wife and daughters. [3][4] Abigail resented her husband's inability to recognize her sacrifices and related his thoughtlessness to the larger issue of the inequality of sexes. She passed this recognition and desire to redress wrongs done to women on to Louisa. Tour of Orchard House, June 19, 2017, C-SPAN. In 1840, after several setbacks with the school, the Alcott family moved to a cottage on 2 acres (0.81 ha) of land, situated along the Sudbury River in Concord, Massachusetts.The three years they spent at the rented Hosmer Cottage were described as idyllic. [5] By 1843, the Alcott family moved, along with six other members of the Consociate Family, [3] to the Utopian Fruitlands community for a brief interval in 18431844. Alcott's early education included lessons from the naturalist Henry David Thoreau who inspired her to write Thoreau's Flute based on her time at Walden's Pond.

Most of the education she received though, came from her father who was strict and believed in the sweetness of self-denial. [3] She also received some instruction from writers and educators such as Ralph Waldo Emerson, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Margaret Fuller, and Julia Ward Howe, all of whom were family friends. She later described these early years in a newspaper sketch entitled Transcendental Wild Oats. " The sketch was reprinted in the volume Silver Pitchers (1876), which relates the family's experiment in "plain living and high thinking at Fruitlands. Poverty made it necessary for Alcott to go to work at an early age as a teacher, seamstress, governess, domestic helper, and writer. Her sisters also supported the family, working as seamstresses, while their mother took on social work among the Irish immigrants. Only the youngest, May, was able to attend public school. Due to all of these pressures, writing became a creative and emotional outlet for Alcott. [3] Her first book was Flower Fables (1849), a selection of tales originally written for Ellen Emerson, daughter of Ralph Waldo Emerson.[6] Alcott is quoted as saying "I wish I was rich, I was good, and we were all a happy family this day"[7] and was driven in life not to be poor. In 1847, she and her family served as station masters on the Underground Railroad, when they housed a fugitive slave for one week and had discussions with Frederick Douglass. [8] Alcott read and admired the "Declaration of Sentiments", published by the Seneca Falls Convention on women's rights, advocating for women's suffrage and became the first woman to register to vote in Concord, Massachusetts in a school board election. [9] The 1850s were hard times for the Alcotts, and in 1854 Louisa found solace at the Boston Theatre where she wrote The Rival Prima Donnas, which she later burned due to a quarrel between the actresses on who would play what role.

At one point in 1857, unable to find work and filled with such despair, Alcott contemplated suicide. During that year, she read Elizabeth Gaskell's biography of Charlotte Brontë and found many parallels to her own life. [citation needed] In 1858, her younger sister Elizabeth died, and her older sister Anna married a man named John Pratt. This felt, to Alcott, to be a breaking up of their sisterhood. As an adult, Alcott was an abolitionist and a feminist.

In 1860, Alcott began writing for the Atlantic Monthly. When the American Civil War broke out, she served as a nurse in the Union Hospital at Georgetown, DC, for six weeks in 18621863.

[6] She intended to serve three months as a nurse, but halfway through she contracted typhoid and became deathly ill, though she eventually recovered. Her letters homerevised and published in the Boston anti-slavery paper Commonwealth and collected as Hospital Sketches (1863, republished with additions in 1869)[6]brought her first critical recognition for her observations and humor.

[10] She wrote about the mismanagement of hospitals and the indifference and callousness of some of the surgeons she encountered. Her main character, Tribulation Periwinkle, showed a passage from innocence to maturity and is a "serious and eloquent witness". [3] Her novel Moods (1864), based on her own experience, was also promising. After her service as a nurse, Alcott's father wrote her a heartfelt poem titled To Louisa May Alcott. [12] The poem describes how proud her father is of her for working as a nurse and helping injured soldiers as well as bringing cheer and love into their home.

He ends the poem by telling her she's in his heart for being a selfless faithful daughter. This poem was featured in the book "Louisa May Alcott: Her Life, Letters, and Journals (1889)".

This poem is also featured in the book "Louisa May Alcott, the Children's Friend" that talks about her childhood and close relationship with her father. In the mid-1860s, Alcott wrote passionate, fiery novels and sensational stories under the nom de plume A. Among these are A Long Fatal Love Chase and Pauline's Passion and Punishment.

Her protagonists for these books are strong and smart. She also produced stories for children, and after they became popular, she did not go back to writing for adults. Other books she wrote are the novelette A Modern Mephistopheles (1875), which people thought Julian Hawthorne wrote, and the semi-autobiographical novel Work (1873). Alcott became even more successful with the first part of Little Women: or Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy (1868), a semi-autobiographical account of her childhood with her sisters in Concord, Massachusetts, published by the Roberts Brothers.

Alcott originally delayed writing the novel, seeing herself incapable of writing a story for girls, despite her publisher, Thomas Niles' urges for her to do so. Part two, or Part Second, also known as Good Wives (1869), followed the March sisters into adulthood and marriage. Little Men (1871) detailed Jo's life at the Plumfield School that she founded with her husband Professor Bhaer at the conclusion of Part Two of Little Women. Jo's Boys (1886) completed the "March Family Saga". Louisa May Alcott commemorative stamp, 1940 issue. In Little Women, Alcott based her heroine "Jo" on herself. But whereas Jo marries at the end of the story, Alcott remained single throughout her life. Because I have fallen in love with so many pretty girls and never once the least bit with any man.[14] However, Alcott's romance while in Europe with the young Polish man Ladislas "Laddie" Wisniewski was detailed in her journals but then deleted by Alcott herself before her death. [15][16] Alcott identified Laddie as the model for Laurie in Little Women.

[17] Likewise, every character seems to be paralleled to some extent, from Beth's death mirroring Lizzie's to Jo's rivalry with the youngest, Amy, as Alcott felt a sort of rivalry for (Abigail) May, at times. [18][19] Though Alcott never married, she did take in May's daughter, Louisa, after May's death in 1879 from childbed fever, caring for little "Lulu" until her death. Little Women was well received, with critics and audiences finding it suitable for many age groups. A reviewer of Eclectic Magazine called it "the very best of books to reach the hearts of the young of any age from six to sixty". [21] It was a fresh, natural representation of daily life. With the success of Little Women, Alcott shied away from the attention and would sometimes act as a servant when fans would come to her house. Louisa May Alcott's grave in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery, Concord, Massachusetts. Along with Elizabeth Stoddard, Rebecca Harding Davis, Anne Moncure Crane, and others, Alcott was part of a group of female authors during the Gilded Age, who addressed women's issues in a modern and candid manner. Their works were, as one newspaper columnist of the period commented, "among the decided'signs of the times'".In 1877 Alcott was one of the founders of the Women's Educational and Industrial Union in Boston. [23] After her youngest sister May died in 1879, Louisa took over for the care of niece, Lulu, who was named after Louisa. Alcott suffered chronic health problems in her later years, [24] including vertigo. [25] She and her earliest biographers[26] attributed her illness and death to mercury poisoning. During her American Civil War service, Alcott contracted typhoid fever and was treated with a compound containing mercury.

[16][24] Recent analysis of Alcott's illness, however, suggests that her chronic health problems may have been associated with an autoimmune disease, not mercury exposure. However, mercury is a known trigger for auto immune diseases. Moreover, a late portrait of Alcott shows a rash on her cheeks, which is a characteristic of lupus.

Alcott died of a stroke at age 55 in Boston, on March 6, 1888, [25] two days after her father's death. Lulu, her niece, was only 8 years old when Louisa died.Louisa's last known words were Is it not meningitis? "[27] She is buried in Sleepy Hollow Cemetery in Concord, near Emerson, Hawthorne, and Thoreau, on a hillside now known as "Authors' Ridge. Louisa frequently wrote in her journals about going on runs up until she died.

She challenged the social norms regarding gender by encouraging her young female readers to run as well. Her Boston home is featured on the Boston Women's Heritage Trail. [31] Her childhood home Orchard House is now a museum that pays homage to Louisa May Alcott and her family that focuses on education. In addition, Harriet Reisen wrote Louisa May Alcott: The Woman Behind "Little Women" which later became a film that was directed by Nancy Porter and aired on PBS television.

In 1996 Alcott was inducted into the National Women's Hall of Fame. Bust of Louisa May Alcott. Little Women or Meg, Jo, Beth and Amy (1868). There is a Part Second of Little Women, also known as "Good Wives", published in 1869; and afterward published together with Little Women. Little Men: Life at Plumfield with Jo's Boys (1871). Jo's Boys and How They Turned Out: A Sequel to "Little Men" (1886). The Inheritance (1849, unpublished until 1997). The Mysterious Key and What It Opened (1867). An Old Fashioned Girl (1870).Will's Wonder Book (1870). Work: A Story of Experience (1873).

Beginning Again, Being a Continuation of Work (1875). Eight Cousins or The Aunt-Hill (1875). Rose in Bloom: A Sequel to Eight Cousins (1876). Jack and Jill: A Village Story (1880).

Behind a Mask, or a Woman's Power (1866). The Abbot's Ghost, or Maurice Treherne's Temptation (1867). A Long Fatal Love Chase (1866; first published 1995). Short story collections for children. Aunt Jo's Scrap-Bag (18721882). (66 short stories in six volumes). Jimmy's Cruise in the Pinafore, Etc. Lulu's Library (18861889) A collection of 32 short stories in three volumes. On Picket Duty, and other tales (1864).Morning-Glories and Other Stories (1867) Eight fantasy stories and four poems for children, including: A Strange Island, (1868); The Rose Family: A Fairy Tale (1864), A Christmas Song, Morning Glories, Shadow-Children, Poppy's Pranks, What the Swallows did, Little Gulliver, The Whale's story, Goldfin and Silvertail. Kitty's Class Day and Other Stories (Three Proverb Stories), 1868, (includes "Kitty's Class Day", "Aunt Kipp" and "Psyche's Art"). A collection of 12 short stories. The Candy Country (1885) (One short story).

May Flowers (1887) (One short story). Mountain-Laurel and Maidenhair (1887) (One short story). A Garland for Girls (1888). A collection of eight short stories.

The Brownie and the Princess (2004). A collection of ten short stories.

Other short stories and novelettes. Pauline's Passion and Punishment. Perilous Play, (1869)(One short story).Lost in a Pyramid, or the Mummy's Curse. Transcendental Wild Oats (1873) A Short story about Alcott's family and the Transcendental Movement. Silver Pitchers, and Independence: A Centennial Love Story (1876).

Little Women inspired film versions in 1933, 1949, 1994, 2018, and 2019. The novel also inspired television series in 1958, 1970, 1978, and 2017, and anime versions in 1981 and 1987. Little Men inspired film versions in 1934, 1940, and 1998. This novel also was the basis for a 1998 television series.

Other films based on Alcott novels and stories are An Old-Fashioned Girl (1949), The Inheritance (1997), and An Old Fashioned Thanksgiving (2008). In 2009 PBS produced an American Masters episode titled "Louisa May Alcott The Woman Behind'Little Women' ". In 2016 a Google Doodle of the author was created by Google artist Sophie Diao. The item "RARE 1870-71 Little Women First Edition Set 2 Parts SIGNED Louisa May Alcott" is in sale since Tuesday, February 4, 2020. This item is in the category "Books\Antiquarian & Collectible". The seller is "dalebooks" and is located in Rochester, New York. This item can be shipped worldwide.- Year Printed: 1870

- Modified Item: Yes

- Country/Region of Manufacture: United States

- Topic: Literature

- Binding: Cloth

- Region: North America

- Origin: American

- Printing Year: 1870

- Author: Louisa May Alcott

- Subject: Literature & Fiction

- Original/Facsimile: Original

- Language: English

- Signed: Yes

- Publisher: Roberts Brothers

- Place of Publication: Boston

- Special Attributes: 1st Edition